What are the criteria set by PHIUS to be considered a Passive House?

Dear Readers,

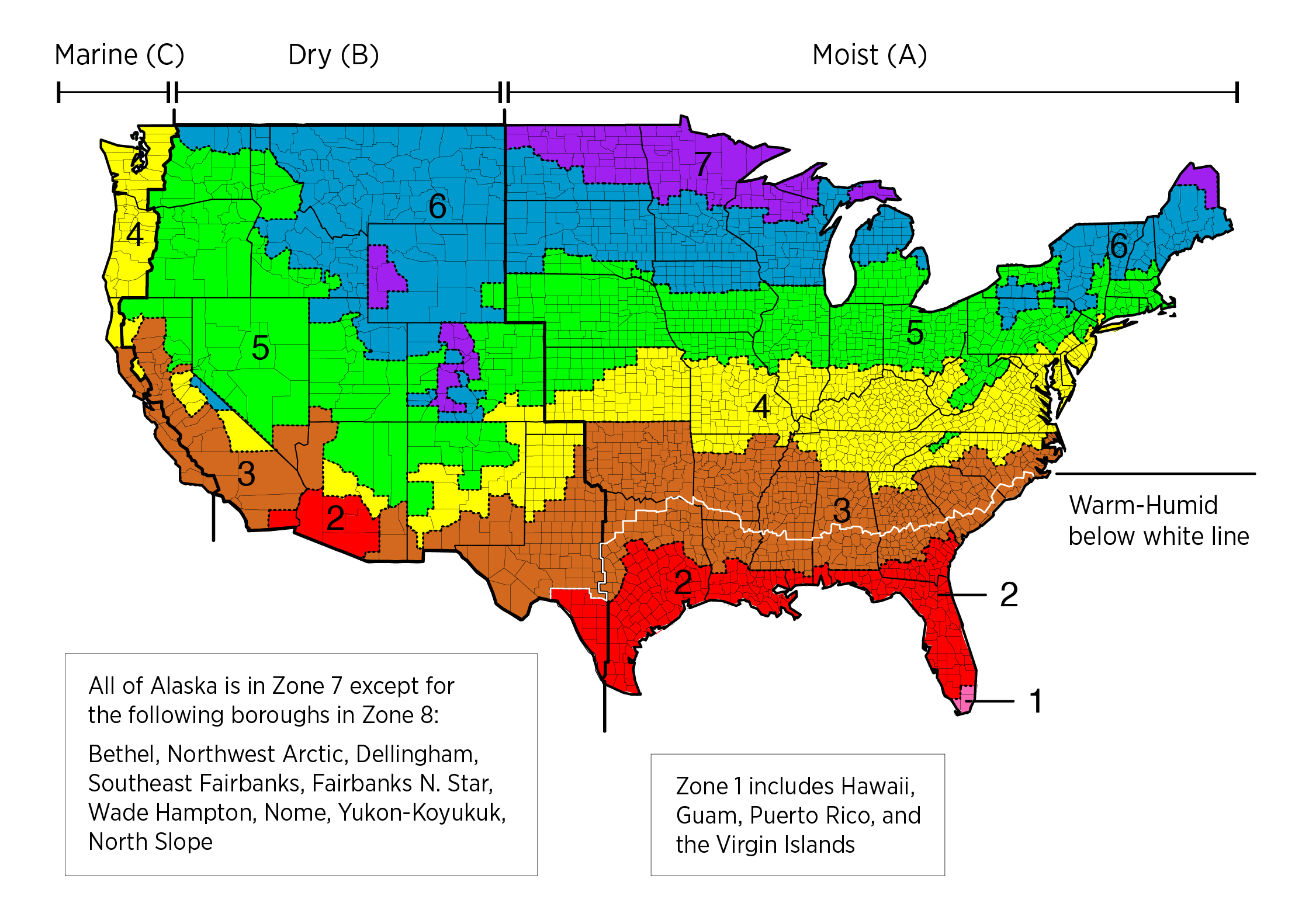

As expressed in Blog Nine, “The Concept of a Passive House Exemplified through a PHIUS Certified Home,” PHIUS sets Passive House criteria according to the climate of the intended home or building. PHIUS uses the North American climate zones set by ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) and the DOE (Department of Energy) as a basis. ASHRAE has essentially eight climate zones which can be additionally broken down into subtype zones: A (Moist), B (Dry), and C (Marine).1 For example, we would build The Seed in climate zone number 5, subtype A.

Source: “2012 IECC- International Energy Conservation Code- Climate Zone Map”, U.S. Department of Energy. https://basc.pnnl.gov/images/iecc-climate-zone-map. Accessed on 12 Jan. 2020.

However, PHIUS gets even more specific than the general zone and subtypes. They offer a free modeling software called “WUFI Passive 3.2,” multiple calculators, and additional modeling tools to calculate requirements for a Passive House, and then help one to design accordingly. One could even pay $75 for a custom generated climate data set to help you find the heating and cooling criteria for your specific address.2

To say the least, PHIUS is fairly well put together, and offers a wealth of information to those interested in building a Passive House. However, for someone who is still trying to fully understand how to use their ‘Space Conditioning Criteria Calculator’… all of the information can get decently overwhelming. So, I have attempted to focus on what PHIUS calls their three main pillars to achieving Passive House standards:

Pillar One: Space conditioning criteria

Space conditioning is the heating or cooling of the interior of your home. According to your home’s size, its occupant density, and the climate of its specific location, PHIUS sets a limit on two specific areas:

- Annual heating and cooling demands

- How much energy your system must exert to heat and cool your home per year.

- The output of heating and cooling is measured in kBtu/sf-iCFA.yr – or, for those of us who don’t speak architecture: ‘kilo (thousand) British thermal units per square foot of interior conditioned floor area per year.’

- Peak heating and cooling loads

- Peak heating load can be defined as how much heat needs to be put out by your system on the coldest day.

- Peak cooling load can be defined as how much cool air needs to be put out by your system on the warmest day.

- The output of peak heating or cooling load is measured in Btu/sf-iCFA.h – ‘British thermal units per square foot of interior conditioned floor area per hour.’

PHIUS sets the criteria with encouragement towards taking passive and “low-grade-energy” measures first.3 Which means, if you insulate your home with ‘Grandma’s knitted sweater-grade insulation,’ and make sure to keep it airtight with that ‘windbreaker,’ the warm or cool air your system is creating will stay in the house. By using passive design, your home will naturally have low annual heating and cooling demands, and low peak loads. Of course, the specific criteria for your home will change according to your climate. A Passive House in Florida will have much different standards than a Passive House in Maine.

Pillar Two: Source energy limit (with encouragement toward zero-energy)

Source energy is the total amount of space-conditioning energy used by your home’s system (both annual and peak) plus all the other energy uses in your home… from your appliances, to the lights, to hot water.4 PHIUS sets the goal in their new 2018 standards with an aim toward net-zero.5 The criteria is not ‘zero energy’ yet, but they are slowly lowering the amount of non-renewable energy a home is allowed to use in order to be considered a Passive House. So! In the future, in order to meet Passive House standards, a home must also be ‘net-zero’– which means William and I are only slightly ahead of the game!

However, PHIUS does recognize that it is unrealistic for all homes to generate all of their own energy. Obvious problems arise such as, there is not enough room on the home’s property for wind turbines… or, the home is not located in the best place for truly efficient solar panels. So, they have allowed some arrangements of procuring off-site renewable energy:

- Directly-owned off-site renewables.

- Example: you own solar panels which are located elsewhere.

- Community renewable energy.

- Example: your town owns solar panels, and you pay them for the energy.

- Virtual Power Purchase Agreements.

- Example: you make an agreement with your utility company to get a certain amount of your electricity from renewable sources.

- Green-E Certified Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs).6

- Example: proof that the energy was generated from a renewable source and then fed into your community’s power system.

The criteria therefore is set according to how much annual source energy is used that is not from renewable resources.

PHIUS sets the limit of annual source energy on a per person basis. Which is interesting, because it truly brings the responsibility of how much CO2 is emitted down to the individual. The reason PHIUS does this is due to ‘fair-share-of-the-atmosphere’ considerations.7 No single person, government, or business has ownership of the atmosphere. As living beings on this earth, we all live in need of oxygen, and we all produce CO2- whether it be from exhaling, or driving a 1998 Jeep Grand Cherokee- we are all in need of clean air. Until it is feasible for all homes to achieve net-zero living and have access to 100% renewable resources, PHIUS sets the annual source energy limit for residential Passive homes at 3840 kWh/person.yr (or, 3840 kilowatt-hours per person per year).8

Pillar Three: Airtightness limit

Airtightness is how well-sealed your home’s envelope is- it is that nifty windbreaker you threw over Grandma’s knitted sweater. If you have leaks in your envelope, your insulation and building structure become susceptible to mold, other moisture problems, and just overall energy loss. Just like the windbreaker: if you have a hole in your windbreaker when it is cold, windy, and rainy, then water will leak in and dampen your thick sweater (thereby creating great discomfort) and much of your body heat will be whisked away by the wind.

PHIUS measures how well-sealed your home’s building envelope is by cfm50 per ft2 (cubic feet per minute at 50 pascals of pressure per square foot). Basically, this measures the amount of air that escapes your home’s envelope whenever it is ‘pressurized’ to 50 pascals.

Pressurized? What? This part is fun. They call it a ‘blower door test.’ They test how well-sealed your building envelope is by shutting all your windows and doors, and attach a very powerful fan to one of your home’s doors. The fan blows air into your house similar to how you would blow air into a balloon. The air looks for escape routes, thereby showing how well-sealed (or, how not very well-sealed) your home’s envelope is.

So, when PHIUS brings the air in your home to 50 pascals by means of that crazy fan, they measure how quickly the air escapes your home to determine if you meet the standard. The airtightness limit for most buildings in PHIUS+2018 is 0.06 cfm50 per ft2 of envelope.9

In conclusion…

All the requirements also take into consideration construction and energy costs of the building’s location, thereby upholding PHIUS’ initiative to promote sustainability in building practices across society as a whole. If building a Passive House is crazy expensive, no individual or business is going to want to do it. PHIUS therefore uses a tool called the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Building Energy Optimization (or, BEoptTM, for short) to program a happy balance of climate specific Passive House building standards, goals for net-zero living, and cost efficiency in construction and maintenance according to the location.

This blog aimed to simplify PHIUS standards into its three main pillars of criteria. For detailed criteria (such as water supply, wastewater treatment, grid electricity inefficiencies, etc.), please see Wright and Klingenberg’s “Climate-Specific Passive Building Standards” and PHIUS’s “PHIUS+ 2018 Passive Building Standard: Standard-Setting Documentation, Version 1.0.”

Thank you, dear readers, for bearing with us as we attempt to explain the basics of Passive House criteria- the foundation of our ideal ideas for our future home! See you next time!

Sincerely,

Shelby Aldrich

1. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). “ASHRAE Climate Zones”. Open Energy Information (OpenEI). March 2011. https://openei.org/wiki/ASHRAE_Climate_Zones. Accessed on 12 Jan. 2020.

2. Passive House Institute of the United States. “Climate Data Sets”. https://www.phius.org/software-resources/wufi-passive-and-other-modeling-tools/climate-data-sets. Accessed on 12 Jan. 2020.

3. Wright, Graham S., and Klingenberg, Katrin with the Passive House Institute of the United States. “Climate-Specific Passive Building Standards”. United States Department of Energy. July 2015. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1220516. Accessed on 1 Jan. 2020. Pages 20-26.

4. Wright, Graham S., and Klingenberg, Katrin with the Passive House Institute of the United States. Pages 19-20.

5. Passive House Institute US. “PHIUS+ 2018 Passive Building Standard: Standard-Setting Documentation, Version 1.0.” 2 Nov. 2018. https://www.phius.org/media/W1siZiIsIjIwMTgvMTEvMDIvM2puNXJ3NnV2cV9QSElVU18yMDE4X1N0YW5kYXJkX1NldHRpbmdfRG9jdW1lbnRhdGlvbl92MS4wLnBkZiJdXQ?sha=1ca3bc8e. Accessed on 13 Jan. 2020. Pages 6-7.

6. Passive House Institute US. Pages 6-7.

7. Wright, Graham S., and Klingenberg, Katrin with the Passive House Institute of the United States. Pages 20-21.

8. Passive House Institute US. Pages 6-7.

9. Passive House Institute US. Page 7.

© 2020 Sustaining Tree

© 2020 Sustaining Tree

0 Comments